Be Inspired by South & East Asian Baking

Happy Lunar New Year, bakers! At BakeryBits we wish you every success in what looks to be an auspicious and exciting year. We've got a super-packed newsletter for you this week, fantastic interviews with bakers around the world explaining Lunar New Year from their perspective. Plus a new recipe for a saffron garlic bread dough made using Asian baking techniques and a combination of white and spelt flours from BakeryBits to give you the most beautiful layered effect. We sell some fantastic saffron and olive oil too - bet you didn't know that - as well as the flour, salt, yeast, baking tins, baking paper - it just needs your excitement to make it happen.

Extra Strong Flours

Marriage's Very Strong 100% Canadian White Bread flour

Matthews 100% Canadian Strong White Flour

two superb roller milled white flours milled extra-fine with

100% high-protein Canadian wheat

So this Lunar New Year – sometimes called “Chinese New Year” though many Asian countries celebrate it, rather than just one – is the perfect chance to celebrate the upsurge in interest in East Asian baking traditions.

At the heart of much of the bread dough made is what bakers in the UK call “strong white flour”, usually milled in steel rollers for the extra fine texture it gives to bread. At BakeryBits we embrace both stone and steel flour milling as they produce flours with different characteristics and uses, and pair very well together. In the UK roller-milled white bread flour is available in two styles: “strong white”, which has a good ability to create a stretchy, resilient dough; and “extra strong”, which is the same but super-powered. I use both white flour types in my baking, as well as stone-milled flours for extra flavour and texture.

Remember: if you can't find the flour, ingredient or equipment you're after then get in touch - click here to email [email protected] - and let us see what we can come up with. Over the years we have built up extensive contacts with many of the world's best artisan millers, craftspeople, equipment manufacturers and suppliers: we can find just what you’re looking for. Send us your baking wish list and we’ll do our magic.

Now one last thing before our Lunar New Year Baking newsletter kicks off: do go to Google and leave us a review if you’ve like what we do. For all small companies like ours it really helps to tell other people what we’re doing right. So if you have the time leave us a review here.

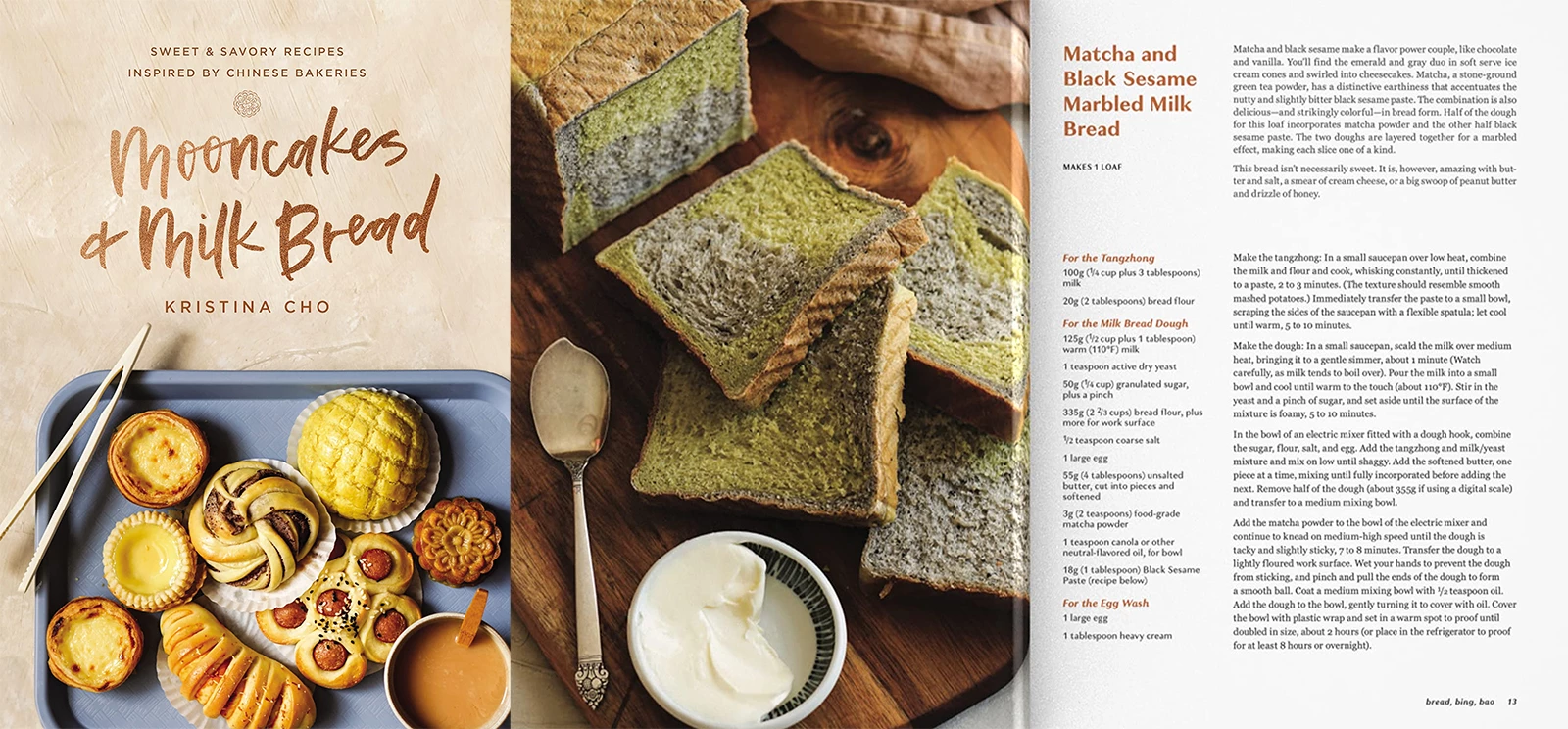

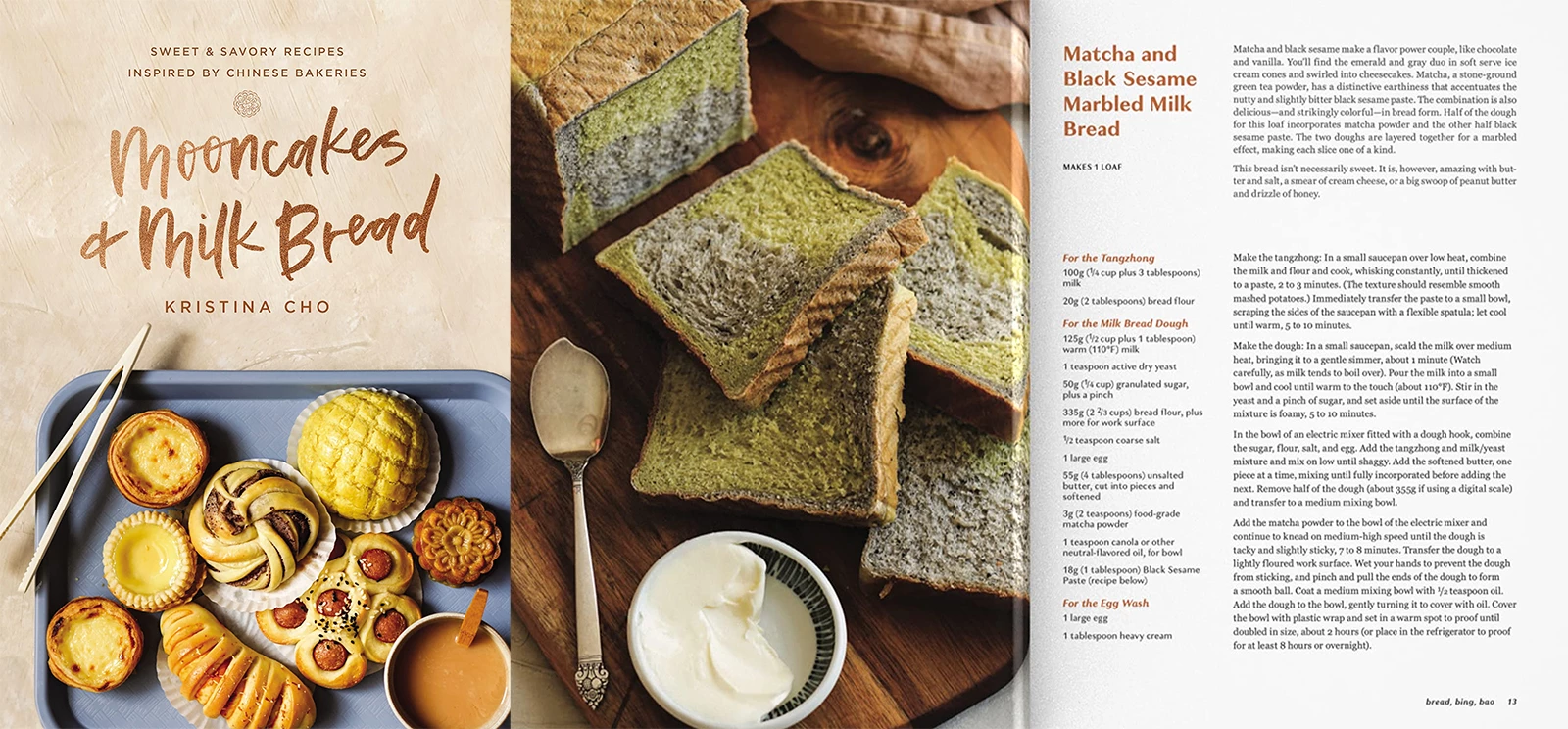

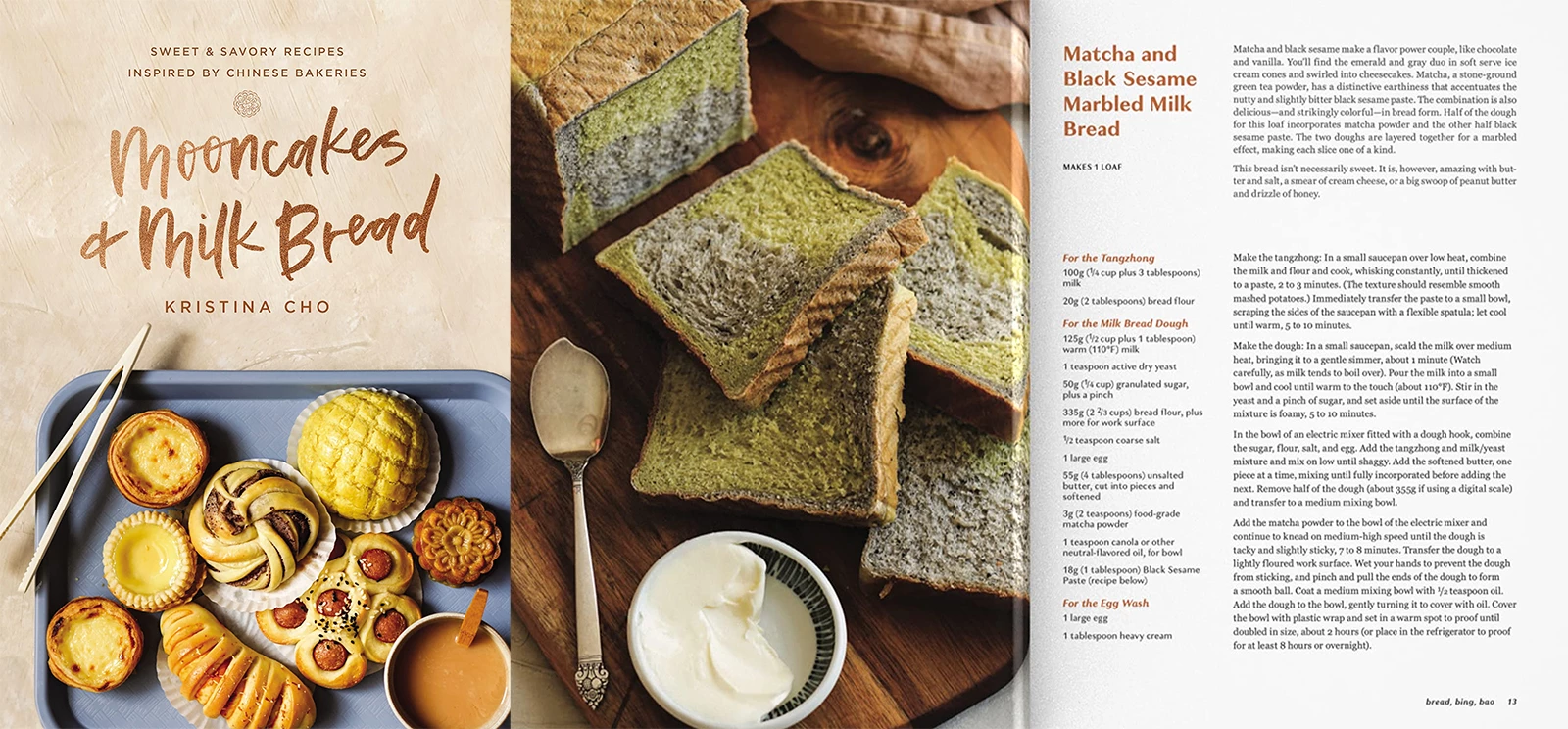

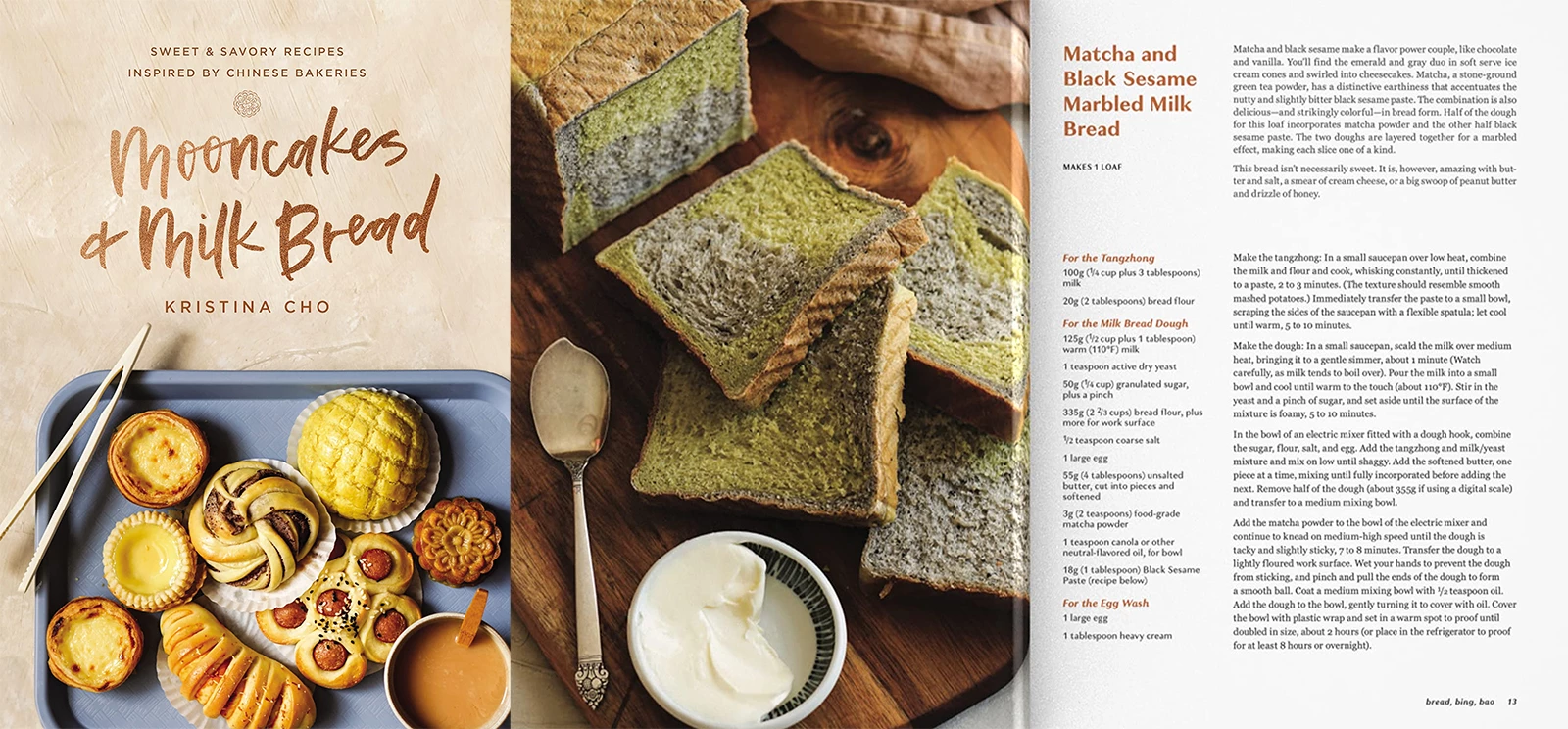

Cover and pages from Kristina Cho's new book "Mooncakes & Milk Bread" (Harper Horizon, 2021)

Kristina Cho, cookbook author, recipe developer, food stylist, and photographer at eatchofood.com. Kristina’s brilliant book “Mooncakes and Milk Bread: Sweet & Savory Recipes Inspired by Chinese Bakeries” is out to rave reviews in the US. The New York Times writes "Cho's book is so smart and thorough”, and Bon Appétit describes it as “filled with both iconic and new-school savory snacks”.

My book sold out as soon as it was released so it was a big surprise, but I’ve just been told that more books have been shipped to the UK so that’s great. Mooncakes & Milk Bread is my very first cookbook, and I am still very honoured that I had the opportunity to write it. Not many people are given the chance to write a book on the first subject that they’re close to, and there’s no other cookbook like it right now out there. It’s the right time for my book, and I only hope it opens up more opportunities for other Asian cooks to write about baking from their perspective – say on Vietnamese baking, Filipino baking. The book covers sweet and savoury recipes, inspired by what I consider Chinese baking to be about, modelled on the Cantonese – Hong Kong style of takeaway bakeries with all the different buns. You walk in and see these glass or acrylic cases, you take a tray and you pick and choose all the different things that you want.

Going to these kinds of bakeries was a really fun childhood memory for me. I grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, which is not a big city in the United States. It’s kind of a small-tier city that didn’t have a big Asian community, and a very teeny-tiny Chinatown. So when we’d go to Chicago or other big cities we’d always stop at a Chinese bakery at the beginning and the end of our trip, so we could start and finish our time away with our favourite buns. And over the years I noticed that I didn’t really see recipes that explained how to make those things that I loved as a kid, or that shared those kind of stories. So on my own blog called Eat Cho Food a few years ago I started sharing different kinds of Chinese-inspired buns, and people were so excited. That’s kind of how I got the inspiration. I started to think, “You know, I think there really are people out there who want recipes like this”.

I think about 40% of the recipes in the book are very iconic for Chinese bakeries. Because this is the first book that has covered this kind of baking I had to have certain recipes - pineapple buns, cocktail buns, for example - to truly be a Chinese baking book. But I wanted to have some recipes that are truly unique creations of my own that show different techniques using the base-dough bread that you’d find in Chinese bakeries but adding parmesan cheese, something really accessible you can buy at your local grocery store so you still feel you’re creating something new and unique in your home kitchen.

But home baking in Chinese culture is relatively new, in a sense. There are some recipes from my grandmother in here, they’re actually all steamed cakes and none of them use an oven. Home baking in Chinese families is not an old tradition. My family is from Hong Kong and a lot of the apartments don’t have ovens at all. But now in my generation, and a little older, especially when people have moved to the United States or other countries and have homes with ovens in them, there’s like this really great culture of home bakers now that are learning to combine their Chinese or Asian influence with their Western upbringing, flavours, things like that. So I think that’s also represented in the book too.

Lunar New Year for me means togetherness. And for me all my family was in Ohio, and I live in California, so we’re very far apart. So I haven’t been able to go home for Lunar New Year for about 8 years. I’ve tried to make it an occasion when I gather with my friends and people I care about who live near me…and cooking more food than you need. It’s about being plentiful, generous, and with the recipes I make, being mindful of some traditions while creating “new traditions” for myself. Like every year I try to make a “new” dumpling filling. Dumplings are a big symbol of Lunar New Year because the more dumplings you eat, the richer you’re supposed to be because they resemble little bags of money.

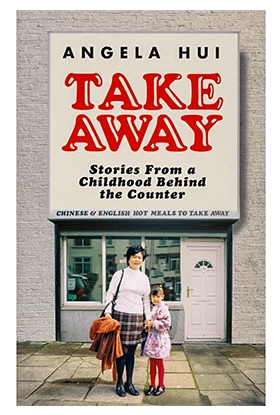

Angela Hui, London-based food & travel writer, for Time Out, BBC, Eater London. Her first book, “Takeaway: Stories from a childhood behind the counter” on growing up in a Chinese takeaway in a small Welsh town, will be published by Orion/Trapeze in July 2022.

At the moment at Time Out, I’m starting to refresh our restaurant section, getting ready for the Year of the Tiger. What I try to do is push out all the fun things there are to do in London, like I’ve seen a lot of great set-menu offers that are around. The “Bun House” boys are doing some really cute steamed buns for Year of the Tiger (with a face and a tail)! There’s a lot of creativity and fun around the food for Lunar New Year, compared to western baking. Say like at Bao Café (in Kings Cross) the sad and smiley faces on buns are really cute. So in terms of the creativity within an Asian bakery there’s a lot more artistic freedom in terms of the way things look. They do play up on the aesthetics a lot more, if that makes sense.

The baker Yvonne Chen has influenced so many people by demonstrating the tangzhong method that is used in so much Asian baking – using flour and water then cooking it first before making the dough – and it’s so exciting that Yvonne is Taiwanese and making this huge difference in Western baking right now. It’s how many people get this very soft amazing texture in milk bread, buns, Japanese white bread, so many things. I tried making quite a bit of it last year when I was bored in lockdown: making lots of milk bread, burger buns, anything really.

My book coming out is basically a food-memoir based on my parent’s takeaway, a coming-of-age story about what life was like in a Welsh Chinese takeaway. It’s 13 chapters and every chapter has a recipe that I had to learn from my mum. I had to learn cooking from my parents who don’t believe in weighing scales, it’s more a bowl of this or a pinch of that. So every recipe is one that she makes, or that I’ve learned from her, or my personal take on her method. The recipes are Chinese takeaway classics, like spring rolls. prawn toast, egg fried rice, things that you’d know from a Chinese takeaway. But there are also recipes that I grew up with, like Cheung Fun (Cantonese rice noodle rolls), my Dad’s pork ribs that he was very reluctant to give the recipe for, and Cantonese soups, so it’s very much a mishmash of British-Chinese food, as well as very traditional Cantonese cooking as well. Each recipe links in through a moment in time in my life.

Gregoire Michaud, the Swiss born, Richemont trained and, for the past 22 years, Hong Kong based pastry chef and baker. Founder of the very popular chain of Bakehouse and Bread Elements retail/wholesale bakeries in Hong Kong.

Though we’re a European bakery in Hong Kong we do a bit of fusion-baking combining Chinese traditions. We’re making pineapple buns right now for Lunar New Year, we’re making some with an apple pie filling, and some with salted duck’s egg yolk, pastry cream and salted caramel. We make our sourdough egg tarts, which are extremely popular: on average my bakery makes fresh and sells 21,000 sourdough egg tarts a day!

It’s a time when people here over-indulge and end up with a fatty liver! Right now there is no travel for Hong Kong residents so people are over-indulging here in Hong Kong as they can’t go around travelling. Which means all businesses in the food industry are thriving. For example, people are buying all these East-Meets-West items to offer as a gift to their friends. So it’s a very busy time for us, and all the local bakeries with their specialities. It’ll make you smile that one of the most popular Lunar New Year gifts here – besides dried seafood, a Hong Kong tradition – are the blue tins of Swedish Butter Cookies, and gold-wrapped Ferrero Rocher. They are everywhere in every household at Chinese New Year. They’re seen as a special gift the same way matcha tea from Kyoto would be viewed as very “exotic” in Europe. So when people buy our baked items as gifts our name adds something, not prestige exactly but we're more unusual and not typical.

Living and working here has changed my view on what tickles and triggers the Hong Kong customers to buy certain items: it’s taken me a very long time to learn and you can’t simply come from the west and assume that everything you do somewhere else will work here. Overly-sweet baking, heavily glazed with sugar, won't work in Hong Kong because it’s just too sweet. Or when it’s too rich and deep fried, fatty and sweet – like doughnut, for example – it won't work. Also people love to see the value of the ingredients. For example, if the surface of a cake is covered in blueberries my customers will love that because they can see the beauty of the fruit on top.

My wife is from Hong Kong, and her family are here, so in our home Chinese New Year is a big event. My mother-in-law is cooking very traditional Cantonese dishes with a lot of seafood. It’s very much like the rest of the year except you buy expensive fish, expensive prawns, expensive clams. You splurge more, basically.

Polly Chan, awarded Royal Academy of Culinary Arts’ Young Pastry Chef Of The Year, is a British-born Chinese baker who set up a micro-bakery kitchen in London in mid-2020 during the UK’s first lockdown, called Polly's Bakehouse, offering freshly baked East-Asian style buns and fresh cream cakes.

As soon as the first lockdown happened in London in 2020 everything was closed, and in Chinatown all the restaurants and bakeries were shut. We couldn’t go out, also, because my mother was high-risk for COVID, but my parents were really craving Asian-style buns, and the only Asian supermarket was quite far from us. So I said to my mother, “I can make them for you, you know I’m a pastry chef and baker”, so I started to make buns, and do some baking trials, to get the right kind of flavour and texture. And after about 4-5 trials I got it, and my mother was like “wow, we don’t need to go to the shops any more”. And by that time things were starting to pick up in the UK, places were starting to open again and we could go out, but I decided to continue.

For us, Lunar New Year means spending time with family, making sure we wish each other well, trying to enter the new year together and healthy, full and happy. We generally all come together for a meal and use specific ingredients: like certain fish, meat and vegetables, because they all mean different things. And we all eat together so that we all share that same idea, and meaning, as we go into the new year together. So I usually bake peanut and almond cookies, and sesame balls – we call them “smiley balls” because when they crack open they create this massive smiley “grin”.

Gan Kim Poh is a Malaysian artisan baker & teacher living in both in Kuala Lumpur and the UK. His Instagram account @gankimpoh was one of the first to stir new interest in panettone and lievito di madre making in South East Asia, and he is considered one of the world’s leading home panettone bakers to rival the best in Italy.

What’s really fun right now is that lots of bakers in Asia are making and selling panettone for Lunar New Year, and it’s quite a logical thing. Panettone making is become very popular, and as a bread it’s good for any occasion. Why only reserve it for Christmas? You can make it with fruits related to Chinese New Year: like kumquat and mandarin oranges, you can candy them. And you know, any way of making business and money during Lunar New Year, people will think of a way to do it.

For Chinese New Year, the most important thing you do, no matter where you are, is that you want to go back and have some kind of reunion dinner with your family. As the world becomes smaller, and your children travel to different places these days, and as the head of the family the mother and father want their children close, to have the dinner together. In the last two years Covid affected many people, we cannot cross borders as Malaysia is divided into different states. In the past year we were not allowed to travel from state to state, but this year the government has allowed it. And I think this will mean a lot to many families, as we learn to live with it and do the best that we can.

It’s very hard you know, especially when you are away, you miss your parents and those relationships, you want to go back and see people. And also Lunar New Year is a good time to meet your other siblings. For most Chinese people, except when it’s not possible, will make the effort to see each other even if it’s only for a dinner. But hopefully Lunar New Year traditions will carry on and encourage family togetherness. and give all your nieces and nephews a chance to meet each other.

It’s also a tradition to wear new clothes. When I was growing up we always looked forward to New Year to receiving hongbao (紅包), the lucky red packet or envelope that you put money in before giving it to someone: you give it to your children, you give it to your parents. You can give it someone who is older but not married. So instead of giving presents you effectively give money, which is much more practical, rather than the European practice of giving a gift that perhaps they don’t want, then people need to return it. Chinese people generally are very pragmatic.

Wing Mon, an exceptionally talented artisan baker, worked and trained at Brickhouse Bread in Dulwich before moving to Paris to work at Ten Belles Bread. Wing returned to the UK and moved to Cumbria where she took up cheesemaking. In two weeks she starts as head baker at Andrew Lowkes' renowned Landrace Bakery in Bath.

It’s funny, I think the longer I bake, the more I feel my opinions on bread have evolved. At the beginning, when I started sourdough baking, I became extremely purist and would really try to stay away from anything super-refined. But I’m British-born Chinese, I was brought up with the standard bakes that you get in a Chinese bakery, which are white and fluffy. And a little bit sweet.

So today I have to say that those things for me are extremely nostalgic. There was probably a point about 5 years ago where I would stop myself from eating those things. Then somewhere along the way, around 2-3 years down the line, I actually just thought to myself, “you know, life’s too short to be that reductionist”.

I guess I’ve wanted to work with interesting bakeries, I would say. I started my career in Manchester with no experience and very quickly learned on the job. And then after working in Manchester for a couple of years I really wanted to go and learn sourdough baking from other people: I’d started from nothing and ended up running something… but I didn’t really feel that I had enough experience to truly be a head baker. So I really wanted to go "somewhere", and back then the only place really to go was London. I fell in love with Brickhouse over Instagram, and contacted Fergus. My real focus at the time was sourdough: I was quite the sourdough purist. I really wanted to work somewhere that was just sourdough and that’s what drew me to Brickhouse, I was really lucky that Fergus took me on there, and then a year after being there I was promoted to head baker. It was an amazing place to work.

So after a few years working there, I was ready for the next challenge. And Ten Belles in Paris was at the time a very unique bakery: though Paris is full of bakeries, Ten Belles is not a very French bakery. That was intriguing to me: it was owned by people who were part-French. Half French – half Irish; Half French – half English; and the third owner was English but had lived in France for a long time. And also, there wasn’t much 100% sourdough in Paris then: a lot of the levain-based bread there would have a touch of yeast added, whereas Ten Belles were making purely 100% sourdough bread. And also making it in a way that wasn’t the typical French style of a pain au levain at the time.

Back then the scale of Ten Belles was quite small, although they knew they wanted to grow. The owners knew I’d done some volume sourdough production work, so it was a kind of great fit for me, and a chance to get more creative, to do slightly different styles of bread so that was a big draw. And also I’d always wanted to live in Paris, and here I had the possibility of doing it. The Brexit vote had just happened, in a few years’ time I wouldn’t have the chance to work there, so it was just like everything was in a line and telling me to go to Paris while I had the chance. So me and my partner thought, yes, lets just go for it. Ten Belles was a great place to work, there was a very good spirit there.